Remu Ogaki, Esq., Senior Project Manager, The CJK Group

It may seem to many litigators that creating search terms across multiple languages is a simple matter of translation.

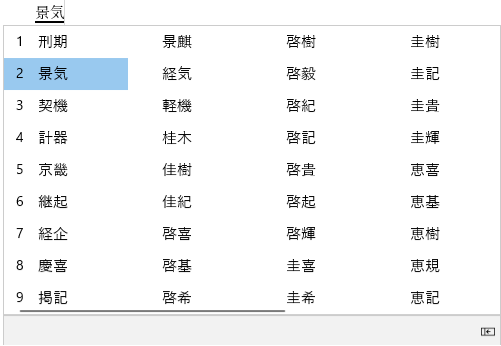

However, when trying to create search terms in a foreign language, there can be unexpected pitfalls that can cause headaches in the form of false hits, unintendedly narrow or broad searches, or missed documents.

In this article, we’ll focus on how the simple task of translating a name can contain unexpected pitfalls. Read the rest of the article at LLM Law Review here:

Rem’s World: Pitfalls in eDiscovery Search Terms and the 10,000 Ways to Write “Kenji Watanabe”